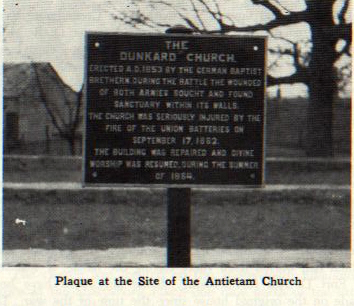

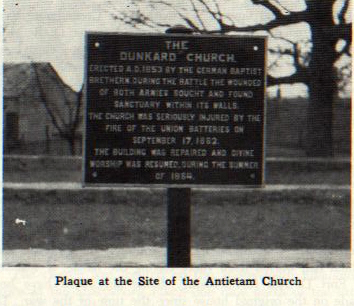

Some time after the battle the metal plaque shown in the accompanying picture

was placed to the right of the front door of the battle-scarred church.

Some time after the battle the metal plaque shown in the accompanying picture

was placed to the right of the front door of the battle-scarred church.from Sidelights on Brethren History, by Freeman

Ankrum,

©1962, The Brethren Press, Elgin, IL, pp. 99-108, reprinted by permission.

Antietam Incidents

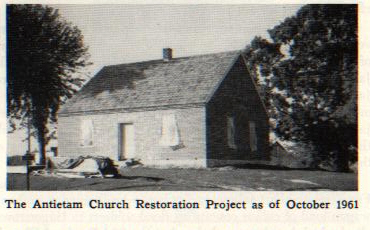

As we stepped upon the large blue limestone threshold we were conscious of the fact that it was much worn - worn by the feet of departed worshipers, curio seekers, and hosts of others who might fall into different classifications. This stone has been in the same place for over one hundred years, having been placed there in 1853 when the church was built. It is not only those worshipers who have departed; the building itself has likewise gone. On that day in May 1921 when the elements were turbulent, it gave way to the storm, and today only the foundation remains. As this chapter is being written, plans are being made for the restoration of the building.

Over the above-mentioned threshold passed the seven deacons who had a part in the erection of the church over one hundred years ago. They were Joseph Wolf, John S. Reichard, Samuel Fahrney, Jacob Reichard, Samuel Emmert, John W. Stouffer, and Valentine Reichard. Samuel Mumma, the man who owned the site and deeded it to these deacons, stepped upon the large blue stone step, also. Over it, David Long, the preacher on that Sunday before the battle in September 1862, entered the church. There is a definite possibility that President Abraham Lincoln stepped upon the stone on his visit to the battlefield in October following the bloody battle. Those among the Brethren whose feet helped to wear down the hard surface were not only Brethren who regularly worshiped there but also those who worshiped at the Manor church. One who might be classed as more or less modern was the faithful John E. Otto of Sharpsburg, who served as pastor for some time.

The "little Dunkard church" on the Antietam battlefield carries the distinction of being bathed in more Civil War history - and also more blood - than any other church. On its benches the wounded and the dying were laid, their blood leaving permanent stains on the wood. Its floors and furnishings were covered with the dust and the rubble which fell from the holes made in the walls by the shells of both armies. From its walls echoed the moans of the wounded, the shrieks of the dying, and the songs of those for whom the war was over. That a church dedicated to peace and goodwill to all men should be a witness to the greatest bloodshed brought about by the strife in our country is indeed ironical. The people who worshiped here in this little white church stood committed against both slavery and war. Strange indeed is it that the battle which did so much to liberate the slaves should almost destroy the house of worship in which their freedom was advocated. That day when President Lincoln is said to have addressed the civilians, soldiers, and officers from the blue limestone steps of the little Brethren church, the sun of freedom shone forth as had always been taught and sought by the Brethren.

The church was located on the Hagerstown Pike (now known as the Sharpsburg Pike), one mile north of the little village of Sharpsburg, which was to give its name to the battlefield as spoken of by the people of the South. This village was in competition with Hagerstown for the rank of county seat, losing out by only one vote. Rich in history, it was laid out on July 3, 1763, by Joseph Chapline. Here James Rumsey, the inventor of the steamboat, lived for a brief period. General Braddock stopped here on his ill-fated expedition to western Pennsylvania. Others who occupied important places in history also spent time here.

On September 16 and 17, 1862, when Lee's forty thousand Confederate troops met McClellan's seventy- five thousand Federal troops, the white-painted brick church stood on the east side of the "west" woods, in a small open space. The west woods covered some seventy-five acres. To the eastward, from the north to the village of Sharpsburg on the south, was farming land occupied by Mummas, Roulettes, Pipers, Millers, Poffenbergers, and others. The church, around which the most severe fighting occurred and around which the tide of battle ebbed and flowed, was within the Confederate battle lines. Three quarters of a mile north, on the D. R. Miller farm, the First Division of General Mead's Pennsylvania Reserves of the First Corps was located with their line extending across the pike toward the west into the Locher woods. From the position beyond the farm buildings the Confederates were driven back to the Brethren church.

Colonel Hawley of the Twelfth Pennsylvania was wounded in this phase of the battle and was carried to the house on the Miller farm, presently owned - by Mr. and Mrs. Paul Culler. Farm boys and others rambling over the farm uncover from time to time relics of the struggle of a century ago. Only recently the Culler family noticed a shining piece of metal which had become uncovered in the basement of their home. Unearthing it, they found it to be a live shell which had buried itself there during the battle; it was sent to Fort Detrick for defusing. Some alterations have been made on the original house since the time of the war. The stone-walled springhouse was recently torn down to make way for the widened and improved highway, but the spring, from which the Boys in Blue and the Boys in Gray carried water, still bubbles forth.

The shell-torn church was restored following the battle, funds for that purpose being solicited by Elder D. P. Sayler. Services were resumed in it in 1864. On May 23, 1921, a heavy storm caused the walls to fall in and the roof to fall down upon the contents of the building. The house which was built on the old foundation following the destruction of the church was removed after the site was purchased by the Washington County Historical Society for restoration purposes.

Some time after the battle the metal plaque shown in the accompanying picture

was placed to the right of the front door of the battle-scarred church.

Some time after the battle the metal plaque shown in the accompanying picture

was placed to the right of the front door of the battle-scarred church.

When the Antietam Battlefield Association (or Commission) some time after the close of the war was marking the different positions of both armies, General James Longstreet was present. A local man asked him what he and his men on the left of their line in the rear of the Brethren church were doing on the eighteenth, the day after the battle. His answer was that they "were cooking coffee and getting something to eat, unconcerned about anything [else]." Asked where he and his officers were when his horse was shot from under him, he answered that he was "by a board fence near the town."

It is related that on the day of the battle, during the hardest fighting near the Brethren church and "Bloody Lane," a man with a two-horse springwagon came to the farm, drove almost to where the observation tower now stands, and gave a number of Union soldiers bread, ham, cakes, and pies that had been sent by some good ladies. No one knows who he was or where he came from. A later effort was made by the War Department to locate him and reward him for his brave effort, but it came to naught.

During the summer of 1911 a party of Confederate veterans came to visit the battlefield. Among them were some of the soldiers who had served under General "Stonewall" Jackson. One of the men said that he was asked by General Jackson, who was located at the Brethren church, to carry a message to General A. P. Hill. He added that before he left Jackson he gave the general, from his canteen, a drink of milk that he just milked a short time before "from a cow back of the Dunkard Church woods."

Martin Snavely, of the John Snavely Belinda Springs Farm, related that following the battle he "hauled a six-horse wagon load of coffins containing dead soldiers to Hagerstown, all of which had been embalmed at the Old Dunkard Church, to be shipped home by friends who had come for them." Hagerstown was the nearest railway station for the North. Mr. Snavely also said the "arms and legs were piled several feet high at the Dunkard Church window where the amputating tables sat." Corroborating this statement, a veteran visiting the field some time later said that as he was passing the church an officer called to him to assist a man loading them onto a cart to haul them away and burn them.

Bloodstains remain to this day on some of the furniture of the church which has been preserved in Sharpsburg. Visitors to the restored church will have the opportunity to see this furniture.

The

section of the field on the Miller (now the Culler) farm just to the north of

the church, known as the Bloody Cornfield, was a part of a field containing

fifty acres, twelve of which had been planted to corn. Nearly every charge

struck  this

field. When night came, the corn, which was fully matured, was trampled nearly

to pieces, nothing but the stalks remaining. Wheat had been in the middle and

clover in the south side of the field, with no fencing between. Probably no

other section of the battlefield was so fiercely fought over. The dead lay so

close together from the church to the east woods that one could have stepped

from man to man without once stepping on the ground. Between twelve hundred and

fifteen hundred bodies were buried in this one field.

this

field. When night came, the corn, which was fully matured, was trampled nearly

to pieces, nothing but the stalks remaining. Wheat had been in the middle and

clover in the south side of the field, with no fencing between. Probably no

other section of the battlefield was so fiercely fought over. The dead lay so

close together from the church to the east woods that one could have stepped

from man to man without once stepping on the ground. Between twelve hundred and

fifteen hundred bodies were buried in this one field.

Only scattered trees stand today in the vicinity of the church. On the day of the battle and for many years afterward the trees were numerous. The bullets imbedded in them afforded sport for the small boy or the curious adult who cared to dig them out. Many of the trees were shorn of their branches by the shells, and were thus left with a stubby appearance.

Samuel Mumma, Jr., lived in the Mumma home near the church. It and the other farm buildings were burned by the Confederate soldiers, after they had been driven from them, to prevent the Union sharpshooters from using them. Mr. Mumma said that "everything except a few small trinkets they [the Mummas] took with them was burned. Two of the daughters, Mrs. Lizzie Grove ... and Miss Alice Mumma, said that when they were told to leave a Confederate soldier who wanted to be gallant offered his assistance in helping them over the fence, but they were very angry because they had to leave and refused his assistance." After the battle the Mumma family went to the Sherrick farm to live.

A report that the Confederates had put salt in the spring at the farm was circulated. But Mr. Mumma said that his father had been to Hagerstown the day before the battle and had brought several sacks of salt home and put them on the floor of the springhouse; when the building was burned the salt fell into the spring. Mr. Mumma further related that his father dragged fifty-five dead horses from his farm to the east woods, where they were burned. One battery alone had twenty-six horses killed near the church.

E. Russell Hicks, a prominent historian of Washington County, states in his brief history of that county: "On October 1, 1862, President Lincoln visited General McClellan, still at Antietam. He rode out to the little Dunker church in an open coach drawn by six white horses; on the back of each was a plumed soldier. Here he addressed a number of civilians and reviewed the badly shot up army. Going to the hospitals, he shook hands with those wounded who were able to see him. In one of the hospitals lay a number of Confederates; when he asked them if they would like to shake hands with him also, they said they would; so he walked among them and shook their hands. The loss of both the Union and Confederate forces at Antietam totaled more than 25,000 men which, added to the Harper's Ferry loss, runs the number to about 40,000. More men, however, fell at Gettysburg, a three days battle. Out of Gettysburg came Lincoln's greatest address; but out of Antietam came his Emancipation Proclamation."

Inasmuch as the Brethren church was used as a hospital, and inasmuch as Lincoln traveled over the battlefield visiting the wounded, it is not an unwarranted stretching of the imagination to believe that he got out of his carriage, stepped on the limestone threshold, and entered the shell-torn and bloodstained church. Knowing what we do of him, we can readily picture him giving hope and cheer to all alike in his kindly and gracious manner. The austerely plain interior of the church, with its old-fashioned pulpit and its unpainted pine benches, must have contrasted greatly in Lincoln's eyes with the luxurious churches in Washington in which he worshiped.

Other churches in the community were also used as hospitals. Among them was the little stone Episcopal church, St. Mark's, which still stands in picturesque grandeur in a hardwood grove north of the battlefield and a few hundred yards southeast of Lappans Cross Roads, leading from the Sharpsburg Pike. It remained, however, for the Brethren church to be more frequently mentioned in dispatches, and to be the goal of more tourists, while it stood, than was any other church connected with the battle. The metal marker prepared by the government and affixed to the building on the right side of the door soon after the battle stands at this writing fixed upon a post at the foundation of the church. This is to be placed by the side of the restored church. Inside the restored church will be displayed, on loan, the Bible carried from the church to New York State following the battle and returned after being away for more than forty years. (See the chapter entitled "John Lewis and the Antietam Bible.")

The Hagerstown Pike, which ran through the battlefield, was nearly new at the time of the Battle of Antietam, having been built in 1856. It was almost ruined during the battle, but the turnpike company later received payment from the government for the damages.

At the east end of Bloody Lane and a short distance from the church site, a stone observation tower now stands, offering a panoramic view of the battlefield. From the tower's eighty-five-foot height the entire battlefield may be seen, and also a portion of the South Mountain battlefield, Boonsboro, and parts of four states - Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia. The view is classed by tourists as one of the finest in this section of Maryland.

This chapter on Antietam incidents could be ended no better than with a production from the hand of the late Elder James A. Sell, the poet of the common man, a native and long a resident of the Morrison s Cove section of Pennsylvania. He is the author of several books of poems. The one reprinted here was named by him "The Historical Church."

"In primal days this house was built

Wherein to worship God.

Within this refuge young and old,

In solemn silence trod.

They came to hear God s word proclaimed,

That tells to one and all

How the whole world was plunged in sin

By Adam s dreadful fall.

"The weary souls on Sabbath days

Came here for peace and rest.

They sang their songs in solemn strains

And found their souls were blessed.

They could not draw the veil aside

To see what is before,

Or tell when they should reach the place

Where trouble comes no more.

"The clouds of war o'er cast the land

And armies marshalled here,

And ‘midst the din and clash of arms

They faced the battle drear.

When cannon belched their redhot breath

And poured their shells and balls,

The sentries found a hiding place

Behind its sheltering walls.

"The war horse left his cruel scars

Upon this shrine of peace,

That mutely pleads in plaintive tones

For strife and war to cease.

The ones who stand for peace on earth

And freedom for the slave,

Will, in better days to come,

Be called the true and brave.

"This temple now in ruin lies

Upon a lonely hill.

The influence of its day and time

The world can never kill.

Its storm-tossed roof and shattered walls -

Memorials of the past -

Are pointing to a better day,

When peace shall reign at last."

Other chapters in Freeman Ankrum's book

related to the battle of Antietam/Sharpsburg and "the little Dunker

Church":

Troubles Over Slavery

David Long: Civil War Preacher

John Lewis and the Antietam Bible

Return to "The Little Dunker Church" page