"

I have

sinned..."

Message preached March 25,

2001

Long Green Valley Church of the Brethren

Glen Arm, Maryland USA

based upon Luke

15:1-3, 11-32

Order

of Worship

He was a janitor making minimum wage at the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology, where some of the best and brightest are trained. The irony of it

all was that he was the smartest one there, a genius, but no one knew it. No one

knew, that is, until he completed an extremely complex mathematical problem left

as a challenge for students on a blackboard. The story behind the 1997 film,

"Good

Will Hunting," revolves around how this prodigious young man is

discovered and discovers himself. The very title of the movie is a play on his

name, Will Hunting, a prodigal prodigy hunting for where he belonged in this

world.

Perhaps youíve known someone like Will, a person who holds great potential

but has squandered it in some fashion. Maybe you are a "Will Hunting."

Sometimes the very word "potential" is a terrifying weight to place

upon someoneís shoulders. Expectations are very high when the sky is the

limit, you know. Many are those who have sought to run away from the message,

which is as irritating as the voice announcing a letter in an email box:

"Youíve got potential."

In my Websterís Dictionary, the words "prodigal, prodigious, and

prodigy" follow one after the other. They all begin the same way, with a

"prod," a drive, a push, a poke. However, where one is stirred in an

extraordinary, exceptional direction, another is driven away from whatís good, toward wasting potential.

A prodigal is someone who has squandered an inheritance, who has allowed wealth

(be it money or talent) to just slip through the fingers. While the difference

between a prodigy and a prodigal is like day and night, the distance between the

two is minimal.

direction, another is driven away from whatís good, toward wasting potential.

A prodigal is someone who has squandered an inheritance, who has allowed wealth

(be it money or talent) to just slip through the fingers. While the difference

between a prodigy and a prodigal is like day and night, the distance between the

two is minimal.

Fortunately for Will Hunting, he encountered a fatherly figure in

Psychologist Sean McGuire, who helped him not to just discover his

"potential" as a "prodigy," but to discover who he really

was as a person. The most poignant scene in this movie for me, was when this

young man finally shed the cloak of his own smart-allecky intelligence (which he

had worn for protection), and was enfolded in the arms of Sean, the caring

father he never had. The prodigal son was headed home.

A few moments ago, we heard again the old, old story Jesus told which

continues to stir us. Maybe, for some of you, that was the first time youíve

ever heard it - a possibility which we should never ignore. As followers of

Jesus in this day and age, itís exciting to know that the message we bear may

be "news" to someone who has never heard it. The joy comes in the

sharing, surrounded as we are by a "community of heavenly celebration"

(Luke 15:7, 10) we often fail to perceive. A "great

cloud of witnesses," (Hebrews

12:1-2) saints

triumphant and angels holy, is part of the process of helping all Godís

children to discover who they really are, no matter in what "far

country" they find themselves. Call it "Godís Will Hunting."

For

the rest of us, however, the struggle of faithful listening when weíve heard

the old, old story many, many times, is to hear in it something new - not

necessarily something that has never been heard before, but something that is

good "news" to us - that renews, that brings about a "new

creation" in us (2 Corinthians

5:17). This

only happens, though, when the words cease to be ink on a page and are, instead,

written upon the human heart - when we enter the story, and allow ourselves to

be prodded by it. Let me set the stage for this drama.

For

the rest of us, however, the struggle of faithful listening when weíve heard

the old, old story many, many times, is to hear in it something new - not

necessarily something that has never been heard before, but something that is

good "news" to us - that renews, that brings about a "new

creation" in us (2 Corinthians

5:17). This

only happens, though, when the words cease to be ink on a page and are, instead,

written upon the human heart - when we enter the story, and allow ourselves to

be prodded by it. Let me set the stage for this drama.

Imagine you are sitting in a room full of prodigies and prodigals, those who

have a gift and are putting it to use, and those who are likewise gifted but

have squandered their inheritance. Thatís how gospel storyteller Luke paints

the backdrop for this parable of Jesus. In this room are "scribes and

pharisees," the prodigies. They stand over on one side. They have invested

themselves in their calling. They are not necessarily bad people, as we

sometimes mistakenly think of them. They seek to do what is right, to live by

the law of Moses. In fact, they are gifted in interpreting Godís will, though

there are limits to their gift - a blindness, even, in their ability to see.

On the other side of the room stand "tax collectors and other

sinners." They are the proverbial squanderers of what God has given,

wasting an inheritance - their own individual versions of "loose

living." No doubt they each could tell a story about how they arrived at

their own "far country." But thatís not why they have come to this

room. No, they have heard hints of love and grace from this rabbi Jesus that

just wonít let go of them. Something is prodding them closer to him, and so

they find themselves in this room also.

An offhand comment starts it all off. Mumbling and grumbling flows from the

"prodigy" side of the room. "This fellow welcomes sinners and

eats with them." Itís one thing to be together in the same room, yet

another to sit at the same table. Donít you know that prodigies and prodigals

are worlds apart?

I found something interesting in my Websterís Dictionary. When I looked up

the word, "prodigy," I found that it comes from the Latin word, "prodigium,"

which means an "omen" or a "monster." In fact, the primary

meaning for "prodigy" has to do with an event, something that is

unusual or extraordinary. Only secondarily is a "prodigy" a

"highly talented child." This may say something about why a child

prodigy can end up squandering their gift. After all, who really wants to be

seen as "different?" Ask our youth. To be different is to be like ...

a monster.

[By the way, we need to be careful as Christians not to twist Jesusí

words to make the "scribes and pharisees" or their descendants out

to be "monsters." For as we will see, the title may just as easily

fit us.]

Anyway, an offhand comment lead to a story from Jesus. He had a habit of

doing that, you know. Actually, according to Luke, it was three stories: about a

shepherd and a lost sheep, about a woman and a lost

coin, and about a father and

a son - or, more correctly, two sons. These are tales of remarkable love and

grace, omens of Godís extraordinary kingdom which is approaching right around

the next bend in the road.

How do we hear this last story? What side of the room are we standing upon as

we listen? You see, weíre no longer onlookers, observing from the safety of

being outside the scripture. No, weíre in the very room with all the rest. So

which are we, prodigies or prodigals? After all, none of us are without a gift

of some sort, something we have inherited in some fashion, something placed into

our hands for some reason. Have we done something with it, or are we wasting it?

As we listen to this story, from one side of the room or the other, we shoot

side glances at those with whom we share the space.

The stage is set. Now, mind you, I didnít say I was going to retell the

story. Youíve already heard it this morning, but were you truly listening? Furthermore, are you going to allow this parable to

"parable" you? Jesus told his stories to turn our world upside-down,

to shift our thinking from "a human point of view" (cf.

2 Corinthians 5:16), to shake us up such that in our dizziness we might

hear God speak what we need to hear, undistracted by our own ability to figure

it all out. You see, sometimes the folks who think they have it all figured out

are just as lost as those who know they donít.

you truly listening? Furthermore, are you going to allow this parable to

"parable" you? Jesus told his stories to turn our world upside-down,

to shift our thinking from "a human point of view" (cf.

2 Corinthians 5:16), to shake us up such that in our dizziness we might

hear God speak what we need to hear, undistracted by our own ability to figure

it all out. You see, sometimes the folks who think they have it all figured out

are just as lost as those who know they donít.

Like the older brother of the prodigal son. He had it all figured out. He

knew what his fatherís gracious welcome of his no-good brother was costing

him. He also had in mind a pretty good picture of how his sibling wasted his

shared of the inheritance. Please note, nowhere in the story does it say exactly

what the younger brother did to lose everything in that far country. All Jesus

said was that "he squandered his property in dissolute (or prodigal)

living." The older brother, when confronted by his father, however, had it

all figured out. He "devoured your property with prostitutes," Dad.

And "you killed the fatted calf for him." Iíve not been wasting my

inheritance, but there is no celebration for me.

Such a sad, sad note the story ends with, for the older brother is just as

lost as his younger sibling. He just canít see it. Furthermore, he doesnít

really know how to celebrate. You see, joy doesnít depend upon everything

fitting together as we think it should. Sometimes we can be so smart that we

miss whatís really real - that what was dead has come to life, what was lost

has been found. Thereís a fresh beginning, a second chance, a new creation -

for all of us, prodigals and prodigies alike. Joy flows as we turn toward its

source.

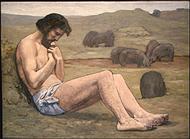

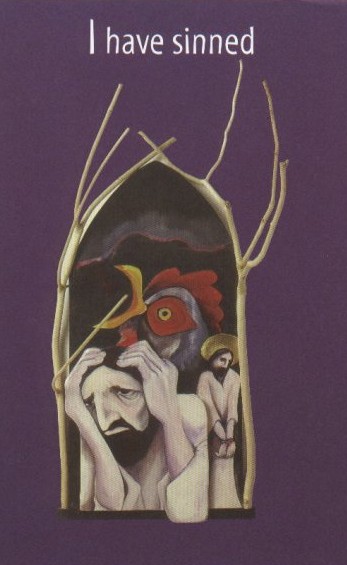

Let

me again draw your attention to the cover of your bulletin. In our journey

through Lent toward Easter this year, one of our guides is Paul Grout, whose

series of paintings entitled, "Stations of the Resurrection" has been

reproduced in part on our bulletins. The seen portrayed on this day is not from

this story Jesus told about a waiting father and his two sons, though Paul has

linked it that parable.

Let

me again draw your attention to the cover of your bulletin. In our journey

through Lent toward Easter this year, one of our guides is Paul Grout, whose

series of paintings entitled, "Stations of the Resurrection" has been

reproduced in part on our bulletins. The seen portrayed on this day is not from

this story Jesus told about a waiting father and his two sons, though Paul has

linked it that parable.

[Bulletin cover art by Paul Grout.

From Church of the Brethren Living Word Bulletin

series,

copyright 2001. Used by permission of Paul

Grout.]

You see, one of the persons in that room full of prodigals and prodigies was

a certain disciple named Peter. He probably, like many of us, would have had a

hard time figuring out on which side of the room he belonged. He was, after all,

a simple man - a fisherman by trade. But the future of what Jesus was starting

would one day rest upon his shoulders. What would he, as well as the rest of the

disciples, do with this inheritance? Would they squander it in some fashion?

Would they figure it all out in such a way as to miss the new thing God was

creating?

Along the way of Jesusí arrest and trial, Peter - who thought he had it all

figured out ("believe me, Lord, Iíll never deny you") - found

himself lost in a far country. When confronted in the courtyard outside where

Jesus had been taken, Peter declared "three time" (even) that he didnít

know this trouble-making rabbi from Galilee. And, as the story we have received

goes, at that moment Peter was parabled, so to speak, by a rooster. It crowed

for the third time itself, fulfilling what Jesus had earlier predicted. (see

Luke

22:54-62) Peter then wept bitterly, and lay hidden, as lost as the prodigal son

or the older brother, until a new day dawned - and Jesus welcomed him and the

rest to come home, to step out into the power of the resurrection.

Had Peter not heard the cock crow, and been devastated by it, I wonder what

wouldíve become of the church he and the rest were called to lead. Would they

have become what God had intended them to be? Would they have been a people to

whom and a place to which prodigals of every stripe could come and be welcome,

and discover who they really were in Christ Jesus?

And

what of us? Is this parable of the waiting father and his two sons our story

also? If so, I invite you to stand with me, and speak the prayer found on the

back of your bulletin - after which weíll re-tell the story in song ("Far, far away from my loving

father").

And

what of us? Is this parable of the waiting father and his two sons our story

also? If so, I invite you to stand with me, and speak the prayer found on the

back of your bulletin - after which weíll re-tell the story in song ("Far, far away from my loving

father").

Prayer: Oh God, I have sinned against you. I turn my heart home to you.

©2001 Peter

L. Haynes

return to "Messages"

page

return to Long Green Valley Church

page

direction, another is driven away from whatís good, toward wasting potential.

A prodigal is someone who has squandered an inheritance, who has allowed wealth

(be it money or talent) to just slip through the fingers. While the difference

between a prodigy and a prodigal is like day and night, the distance between the

two is minimal.

direction, another is driven away from whatís good, toward wasting potential.

A prodigal is someone who has squandered an inheritance, who has allowed wealth

(be it money or talent) to just slip through the fingers. While the difference

between a prodigy and a prodigal is like day and night, the distance between the

two is minimal. For

the rest of us, however, the struggle of faithful listening when weíve heard

the old, old story many, many times, is to hear in it something new - not

necessarily something that has never been heard before, but something that is

good "news" to us - that renews, that brings about a "new

creation" in us (

For

the rest of us, however, the struggle of faithful listening when weíve heard

the old, old story many, many times, is to hear in it something new - not

necessarily something that has never been heard before, but something that is

good "news" to us - that renews, that brings about a "new

creation" in us ( you truly listening? Furthermore, are you going to allow this parable to

"parable" you? Jesus told his stories to turn our world upside-down,

to shift our thinking from "a human point of view" (cf.

you truly listening? Furthermore, are you going to allow this parable to

"parable" you? Jesus told his stories to turn our world upside-down,

to shift our thinking from "a human point of view" (cf.

Let

me again draw your attention to the cover of your bulletin. In our journey

through Lent toward Easter this year, one of our guides is Paul Grout, whose

series of paintings entitled, "Stations of the Resurrection" has been

reproduced in part on our bulletins. The seen portrayed on this day is not from

this story Jesus told about a waiting father and his two sons, though Paul has

linked it that parable.

Let

me again draw your attention to the cover of your bulletin. In our journey

through Lent toward Easter this year, one of our guides is Paul Grout, whose

series of paintings entitled, "Stations of the Resurrection" has been

reproduced in part on our bulletins. The seen portrayed on this day is not from

this story Jesus told about a waiting father and his two sons, though Paul has

linked it that parable. And

what of us? Is this parable of the waiting father and his two sons our story

also? If so, I invite you to stand with me, and speak the prayer found on the

back of your bulletin - after which weíll re-tell the story in song ("

And

what of us? Is this parable of the waiting father and his two sons our story

also? If so, I invite you to stand with me, and speak the prayer found on the

back of your bulletin - after which weíll re-tell the story in song ("