|

|

“Science and Caring”

Message preached on

November 18, 2018

by

Dr. David Sack

Long Green Valley Church of the Brethren

Glen Arm, Maryland USA

based upon

1 Kings 17:8-16 and

Luke 8:49-56

|

Note:

this recording begins with an introduction by

Dr. Virginia Berninger (Ginger, a new member at LGV, recently

retired and moved to Baltimore). Unfortunately, something went

wrong with the recording of David's message. We amplified it, but

the quality is bad. David gracously shares his manuscript below,

with pictures from his powerpoint... In answer to David's question concerning whether this constitutes a sermon - we answer, "yes." He is a witness. We (the people) are more than consumers of sermons. "Liturgy" means "the work of the people." We complete the message as we listen - working at engaging our faith. As David, a deacon in this church, encourages below - we seek to make connections,with others, commit ourselves to the path upon which we are called, and care compassionately. |

First , thank you for this invitation to provide this sermon today! I must

apologize about the term “sermon” since I have never given a sermon and am

not even sure how to structure one.

My father was a pastor in the EUB church and he later became a

Mennonite pastor and a seminary professor.

I do have a complete file cabinet in my basement of his sermons –

it would be interesting to pull out one of these to see how well it would

fit today’s world. And you

probably know that my daughter, Rebecca, is a pastor and is very a very

skilled speaker, but it would not be right to steal one of her sermons.

So while I do not give sermons, I do give lectures at the Johns

Hopkins School of Public Health where I teach the students about tropical

diseases like leishmania or neurocysticercosis.

I doubt you would find these very interesting; they often include

disgusting pictures and discussions on causes of diseases, cures and

calamities and can go on for about 1 ½ hours.

So, I will try to limit my time to less than a full lecture period. I was

asked to explain a bit about what I do when leave Maryland and go to

different parts of our world.

What do I do, what do I observe, and why am doing this?

When I say, “my” work and travels, I obviously include Jean in this

since our careers are very much a joint effort.

The title of the talk is “Science and Caring”.

Through this topic, I am trying to link two parts of my world that

sometimes seems distinct, but in fact are very much two sides of the same

coin. Also through this

topic, I was hoping to tell you a bit about what I do during my trips and

share some perspectives of the motivations behind our work.

As a physician, I used to practice medicine with a specialty in infectious

diseases. Early in my career after witnessing death by preventable

diarrheas in the Congo, I felt that a research on treating and preventing

killing diseases was the direction I should take.

This is a different life style that the normal practice of

medicine; it involves applying for grants, doing lab and field

experiments, writing papers for journals, and, of course, teaching and

mentoring. A medical

researcher pursues new knowledge, and is always looking for new ways of

thinking, and intends to apply scientific methods to find better

treatments or new vaccines. I hope

that this time this morning will allow me to explain a little of what I do

as a scientist but also how this public health research helps us to

understand what it means to care.

So, my sermon today is part travelogue, part a “moment for mission

time,” part an explanation of some research, and part a perspective on the

concept of caring that i think I have learned through my career.

During my talk I will alternate between experiences in Bangladesh,

Africa, and at Long Green to see how these relate to the ideas of caring.

_------------------------------slides on--------------------

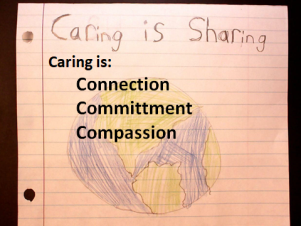

How would you define caring?

Here is one child’s idea of caring.

But what words would you use for this picture?

To illustrate one view of caring, I will show a short video clip from

Bangladesh where Jean and lived and worked for many years.

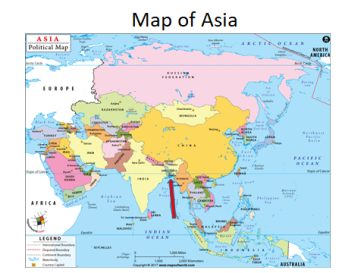

For those who may not remember where Bangladesh is, it lies between

India and Myanmar (Burma). It

is a small country, about the size of Florida, but has a very large

population – about 170 million.

Most of the country if barely above sea level, so with climate

change about 1/3 of the country will soon be under water soon.

Because of its poverty, its crowding, and its Ganges Delta

environment, this is the homeland of cholera.

To illustrate one view of caring, I will show a short video clip from

Bangladesh where Jean and lived and worked for many years.

For those who may not remember where Bangladesh is, it lies between

India and Myanmar (Burma). It

is a small country, about the size of Florida, but has a very large

population – about 170 million.

Most of the country if barely above sea level, so with climate

change about 1/3 of the country will soon be under water soon.

Because of its poverty, its crowding, and its Ganges Delta

environment, this is the homeland of cholera.

You may recall that much of my research has to do with this disease, You

probably know that cholera is a really bad disease, and that outbreaks

have been occurring in many places, but you may not know too much about

details of the disease.

Cholera is a bacterial infection of the intestine.

People become infected when they eat or drink food or water that is

contaminated with the cholera bacteria. This occurs where there is unsafe

water and poor sanitation. A day

or so after drinking the contaminated water, a patient develops the worst

case of diarrhea you can imagine.

This is not just an inconvenience; without treatment, it is fatal

about 50% of the time because the patient loses so much fluid in such a

short time, he goes into shock and dies. It

can happen to anyone, any age, no matter how healthy you were in the

morning – you could be dead by evening. To give you an idea of cholera

patient, I want to show you a short video that was taken at the hospital

in Bangladesh where I was the director.

----------------------Video

of cholera patient -----------

----------------------Video

of cholera patient -----------

In our discussions about health care, we often talk about access to

care. We say health care

should be “available” to everyone, but even here in America, I am often

asked if am able to help facilitate an appointment to see a certain doctor

because the there are no appointments available for 4 months. If that

happens in the US, can you imagine, if you are a poor person in Bangladesh

with a desperate illness, or if your baby is sick and you really need help

immedaitely, you need a “connection.”

If you need the help quickly, this is when the difference between

rich and poor is really evident.

The difference between rich and poor is not just how much money you

have, but whether you have the right connections.

In our discussions about health care, we often talk about access to

care. We say health care

should be “available” to everyone, but even here in America, I am often

asked if am able to help facilitate an appointment to see a certain doctor

because the there are no appointments available for 4 months. If that

happens in the US, can you imagine, if you are a poor person in Bangladesh

with a desperate illness, or if your baby is sick and you really need help

immedaitely, you need a “connection.”

If you need the help quickly, this is when the difference between

rich and poor is really evident.

The difference between rich and poor is not just how much money you

have, but whether you have the right connections.

Caring insists that you help to make these connections with those who are

vulnerable. This leads to a

second story also from our time in Bangladesh.

I had just left Dhaka to attend a meeting in Europe when both a

personal and a political crisis occurred.

We lived in a house in a neighborhood of Dhaka where Jean and the

children remained behind. The

evening after I left, the night guard came to our door begging for help.

His daughter, a married teenager was pregnant and had been in labor

for 2 days, but the baby could not be delivered.

The traditional birth attendant had decided the baby would not

survive, so to save the mother’s life, the traditional midwife was going

to deliver the baby in a way that would kill the baby.

Fortunately, Jean knew some people and was

able to call Dr. Suraiyah, a

military obstetrician, who agreed to take care of her.

The pregnant mother went to the military hospital where she had a

C-section and miraculously, both mother and the healthy baby boy were

saved. One would think this is the end of the story, however, at about the

same time, a group of military officers attempted to take over the country

through a military coup. They

began killing other military officers who would not go along with their

coup plans, and they came to the hospital OB Ward where the mother and

newborn were recovering. They

threatened to kill the obstetrician if she did not join them, but Dr.

Suraiyah said that she was too busy taking care of her emergency patient

and could not be involved. So

it turned out that the doctor saved the lives of the teenaged mother and

baby, and they, in turn saved the life of the doctor.

Twenty years later, we were reintroduced to the mother and her

grown son, and both were doing well.

What does this have to do with caring?

We can say that we care, but without the personal connection,

caring seems empty.

Connections occur here at Long Green as well.

I remember so vividly, our anointing services last week with Floyd

and with Lucille as well as my own anointing nine years ago.

Remember how we “connected” with them by placing our hands on them

and through a chain of hands and connections, we were all connected in our

prayers for them. I cannot

speak for everyone, but I find these connections to be so meaningful.

Do you also notice that when we come to in our church’s entrance door on

Sundays, our greeters welcome you with a gentle hug and the ushers welcome

with a handshake, and sometimes with a second hug.

We feel connected with each other through these simple gestures

that bridge the gaps of isolation.

Have you noticed that the persons who are the ones who shoot people in

these mass killings are often described as “loners?” They seem to have no

other real friends and no connections with other people - other than these

artificial connections through the internet.

I want to show another short clip of Nurse Costa who you saw in the

earlier video caring for Mohammad Subo.

In this video, she talks about her connections to her patient and

what these connections means to the patients and what it means to her.

-------------------------video – Nurse Costa ---------------

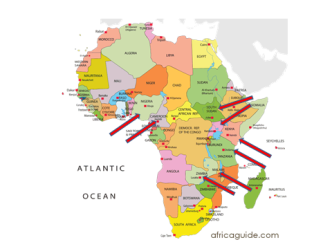

Now, I want to switch gears and take you to a location where I have been

working more recently.

Actually, we and our group have been working in several countries in

Africa.

The map points out the countries where we have projects.

In September I was in Uganda for the launch of a cholera vaccine

campaign along the River Nile.

Last month I went to Cameroon to initiate a research study with the

vaccine there, and then on to Zambia where a similar study is ongoing.

Next month, I’ll be going to Nigeria to work the Mnistry there on

methods to control cholera.

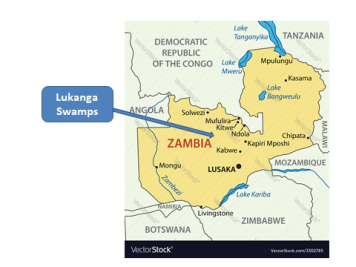

But I want to now talk about the work in Zambia and will relate a story

about the second “c” word that relates to caring: that of

commitment.

This is the story of our oral cholera vaccine project in the Lukanga

Swamps, a very remote area of Zambia, north of Lusaka where we work with a

group of scientists from the Center for Infectious Disease Research in

Zambia (CIDRZ). This is a

Zambian organization that has several projects, and they mainly support

the HIV-AIDS program. This is

largely funded through the PEPFAR program that was started under President

George Bush to provide HIV treatment to millions of people living in

Africa. It is an amazingly

successful program which provides opportunities for many very committed

people. (Actually, I have seen the same program operating in Uganda and

Tanzania, so the taxpayers of the US should be very proud of this very

successful program which is saving the lives of literally millions of

people.)

This is the story of our oral cholera vaccine project in the Lukanga

Swamps, a very remote area of Zambia, north of Lusaka where we work with a

group of scientists from the Center for Infectious Disease Research in

Zambia (CIDRZ). This is a

Zambian organization that has several projects, and they mainly support

the HIV-AIDS program. This is

largely funded through the PEPFAR program that was started under President

George Bush to provide HIV treatment to millions of people living in

Africa. It is an amazingly

successful program which provides opportunities for many very committed

people. (Actually, I have seen the same program operating in Uganda and

Tanzania, so the taxpayers of the US should be very proud of this very

successful program which is saving the lives of literally millions of

people.)

Although this institute mainly deals with HIV, our project in the Lukanga

Swamps is a research project to determine the proper dose interval for the

cholera vaccine. Two doses of

vaccine is supposed to be given of this vaccine which is given by mouth,

but it is not clear if the timing between the two doses should be short

(like two weeks) or whether the interval should be longer (like 6 months).

The team from the institute travels to the field and engages with

fishing communities who live in the Swamps to help with the project.

These communities recently had a large cholera outbreak, so are

very motivated to find a way to prevent the disease.

Their high risk for cholera is because, being fishermen, they

literally live on the water.

I want to quickly show you some photos of clinic, where people live, and

the people who make the project successful.

And, I really want to

stress the commitment of the staff from the institute, especially Caroline

Chisenga – and the people in the village who are willing to participate in

the project, including getting blood samples taken several times.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I especially want to highlight the commitment of this fisherman who is

also working for our project.

His name is Friday Mwape and he is pictured here with his two, very

dressed up sons, but who are also fishermen.

His sons developed cholera while out fishing, but Friday recognized

the symptoms and got them to treatment in time. They both survived.

He is now one of the people who is really committed and is

promoting the cholera prevention strategies – not just vaccine but also

the importance of clean water.

So how does this project illustrate a caring commitment?

Here we are in Baltimore, a distance of 7,730 miles from Lusaka (I

checked this distance on the web) the capital of Zambia, and Lusaka is a

day’s drive to the Lusaka Swamps, and yet we are committed as well as

connected in the common goal of ending the cholera threat for the people

in Lukanga and through this project to people living in other countries in

Africa.

I hope you saw the commitment on the faces of the field workers to their

task. These are not well

educated people, but they are very intelligent and are determined to do

their best job to make this project a success – they know their lives and

the lives of the others in their communities depend on it.

We sometimes think that our Brethren in Nigeria are far away, but we are

still connected to these very committed Christians.

I should mention another person I met while working in the Far

North Region of Cameroon. Dr.

Rebecca recently retired but was the Director of the Cameroon Ministry of

Health in the Region (there are seven such regions in Cameroon).

Not only is she the head of the health department, she is also a

deacon in the Brethren Church. Recall that this area, is next to northern

Nigeria, which is an area threatened by Boko Harum.

Unfortunately, I am not able to travel to this area because of the

security issues, but she and the church remain committed to helping the

people, most of whom are Muslims.

We sometimes think that our Brethren in Nigeria are far away, but we are

still connected to these very committed Christians.

I should mention another person I met while working in the Far

North Region of Cameroon. Dr.

Rebecca recently retired but was the Director of the Cameroon Ministry of

Health in the Region (there are seven such regions in Cameroon).

Not only is she the head of the health department, she is also a

deacon in the Brethren Church. Recall that this area, is next to northern

Nigeria, which is an area threatened by Boko Harum.

Unfortunately, I am not able to travel to this area because of the

security issues, but she and the church remain committed to helping the

people, most of whom are Muslims.

Here at Long Green, people who demonstrate commitment generally do not

want to be pointed out, so I will avoid naming names, but without them, we

would not be able to care for each other or for our neighbors. This is

especially emphasized with Pastor Pete’s temporary disability, so many of

you have made an extra commitment.

We have discussed two aspects of caring: namely connection and commitment,

but now I would like to take you back to Bangladesh again to relate a

couple of additional stories that relate to the final “c”

word which helps me to understand caring; This is the word

compassion. While I

show this photo, I need to tell you the backstory of what this grandmother

is doing with her grandson.

She is giving him oral rehydration solution, otherwise known as ORS.

This simple mixture of sugar and a combination of some electrolytes

was actually developed in Bangladesh at the institute where I worked.

We have discussed two aspects of caring: namely connection and commitment,

but now I would like to take you back to Bangladesh again to relate a

couple of additional stories that relate to the final “c”

word which helps me to understand caring; This is the word

compassion. While I

show this photo, I need to tell you the backstory of what this grandmother

is doing with her grandson.

She is giving him oral rehydration solution, otherwise known as ORS.

This simple mixture of sugar and a combination of some electrolytes

was actually developed in Bangladesh at the institute where I worked.

The medical journal Lancet wrote that ORS was the most important medical

development of the 20th century because it has saved millions

of lives, more lives than any other therapy and it costs only pennies.

The science and research that went into its development actually involved

a considerable amount of high-tech biochemistry and physiology, involving

glucose mediated transport of sodium, balance os osmolarity, and others

concepts, but the final outcome is a simple electrolyte salt and sugar

solution which is used all over the world.

Can a scientific research project be described as compassionate?

Certainly the discovery that saves so many lives does seem

compassionate, but when you see the result also leads to this

grandmother’s ability to treat her grandson by herself – without the

needles, IVs, tubes and machines that are so common in our western medical

system – I believe this ability of families to save their sick children

with ORS also shows compassion.

One final story about compassion.

When we were in Dhaka, I talked with a pregnant mother of a baby

who was being treated in the nutrition rehabilitation unit of the

hospital. The photo is not of

this mother, but shows a similar image of a

severely malnourished infant.

The date I visited with them was December

4, 2003.

One final story about compassion.

When we were in Dhaka, I talked with a pregnant mother of a baby

who was being treated in the nutrition rehabilitation unit of the

hospital. The photo is not of

this mother, but shows a similar image of a

severely malnourished infant.

The date I visited with them was December

4, 2003.

I asked the mother, named Aliya, about the health of her 12 month

baby girl who weighed 10.5 pounds (this is less than half of expected

weight for this age). Aliya

told me that she was 30 years old but had never been able to attend

school. Her husband was a day

laborer, meaning that every day he tries to find a job for the day.

She and her husband live in a one room house in a Dhaka slum; it

does have electricity and a cement floor, but no other modern

conveniences. They share a hand pump for water and a latrine with ten

other families. They had

lived in the rural area, but he could find no work there so they moved to

the city of Dhaka. She told

me that this was her fourth baby, but each of the previous three babies

had died. Her first child, a

girl, died at age 3 when she fell into a pond in the village and drowned.

The second, a boy, developed bloody dysentery at age 18 months.

There was no doctor where she lived, but she saw a village doctor

(called a Kobiraj) who gave him some medicine, but it was not effective so

their son perished. Aliya’s

third, baby girl died of tetanus when she was 20 days old.

So many of the issues of the public health are illustrated in this one

family. Three of four

children have died, and now she was pregnant again.

The surviving child has a chance now that she is in the nutrition

unit, but otherwise would certainly have died.

Mothers education, drowning, dysentery, vaccine preventable

infections like tetanus, malnutrition, family planning, and lack of good

medical care are among the leading causes of death of children in

Bangladesh. Through talking with

mothers like Aliya, we can gain understanding about the unmet needs of the

people, and this should guide what scientific research is needed most.

Through this understanding, policy makers can actually make

compassionate decisions about what medical research to fund.

I do not want to get too political, but I believe that this public health

approach really should be stressed for the USA.

When we look at the research dollars that are devoted to different

health conditions it is clear that

where we spend our research dollars to not match the public health

problems we face. A good

example of this is the lack of funding for Alzheimer’s which afflicts so

many. A more compassionate

understanding would certainly change this.

Here I have given almost an entire sermon but I have not yet referred to a

scripture passage – except for the scripture readings you heard earlier.

I was hoping I could find a Gospel

passage when Jesus carried out a clinical trial to see how to cure people

in the most cost effective manner.

I was not able to find this scripture, but I am willing to bet that

nearly all of us can recall the times that He connected with people: with

outcasts, with women, with lepers, Romans, Canaanites and Samaritans, with

tax collectors, with the multitude in the hills.

His commitment to teaching and preaching was clear, including his

commitment to the cross. And

what stories do you have for compassion: “suffer the children,” “Jesus

wept,” what other stories show compassion?

What are the lessons of caring for Long Green today?

We certainly attempt to be a caring church, but maybe there are

lessons to help us monitor our caring. We

provide transportation, meals, comfort, calls, cards; we work in healing

professions and as teachers; we study to plan for service jobs; we anoint

the sick and provide canned goods to food pantries, health and school kits

and CROP funds. After the church

service today, some of us will connect with each other during Sunday

School time, and I trust that nearly all will be staying to celebrate the

joy of a Thanksgiving Meal with each other.

In all of these ways, we show our caring through being

committed, connected and

compassionate.

|

Links and Credits

The web

site for David's project at Johns Hopkins.

The institute in Dhaka is the

International

Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b).

David and Jean lived in Bangladesh three times (1977-80,

1984-87, and 1999-2007).

He was the Director during the last period. The current

director is John Clemens. The web site for the Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia (CIDRZ).

The link to the video with the story of Mohammad Shubo and the

testimony of Nurse Costa is included in

this feature program from Al Jazeera in 2011 (after David and

Jean had left Dhaka).

The entire video is about 30 minutes long, but it is very well

done – probably the best description of cholera and the public

health problem it represents.

Photo credits for almost all the pictures in the powerpoint go to

the professional photographer, Karen Kasmauski -

her

website. She has published in National Geographic and

published books using her photography.

She went to Zambia and earlier went to Bangladesh.

(“The only photo that I actually took,” David says, “is the

one of the

grandmother giving ORS.”) |

©2018

David Sack

(you are welcome to borrow and, where / as appropriate, note

the source - myself or those from whom I have knowingly borrowed.)